Listening to Detroit’s Untested Sexual Assault Kit Survivors and Advocates to Improve Future Victim Notifications

February 2, 2023 - Shelly DeJong

NOTE: This story refers to situations that may trigger traumatic memories for members of our community. Resources and assistance are available through multiple campus programs.

A team of Michigan State psychologists, including Drs. Rebecca Campbell and Katie Gregory, recently concluded a major 3-year study looking at the victim notification process for Detroit’s untested sexual assault kit survivors on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Violence Against Women. This study provides guidance to a variety of teams, including lawyers, law enforcement, and advocates, who are tasked with notifying sexual assault survivors and potentially asking them to participate in the re-opening and prosecution of their cases.

“Our findings suggest that integrating confidential community-based advocacy services into all aspects of the notification and re-engagement process is critical for supporting survivors’ well-being and promoting justice,” said project lead Dr. Katie Gregory.

This project, the most comprehensive study to date on re-engaging with victims who have had a DNA match in the FBI’s national criminal database, CODIS, is part of a long-term collaboration with Detroit to address their untested sexual assault kits.

In 2009, 11,303 sexual assault kits were discovered in a Detroit Police Department warehouse. These kits spanned 30 years, from 1980 to 2009. This discovery didn’t just happen in Detroit--all over the nation cities were finding their own stockpiles. It is estimated that over 200,000 rape kits went untested across the country.

With the help of government funding, many cities are now testing their older sexual assault kits, which raises a new issue: how should victims be informed that their sexual assault kit hadn’t been tested but now has?

The final report states that the notification process “raises complex issues for sexual assault survivors as these traumatic events in their lives are revisited. Advocates need empirically based recommendations for how best to serve this vulnerable population.”

To give these recommendations, the team knew they needed to hear from the Detroit victims themselves.

The researchers partnered with Avalon Healing Center, a community-based sexual assault victim service agency that has been a key partnership in Detroit’s effort to resolve their untested sexual assault kits, to develop a protocol to begin reengaging with the sexual assault victims so their voices could be heard throughout the study.

Throughout the process, they conducted qualitative interviews with 32 sexual assault survivors who all had experienced a CODIS DNA match, had been notified by law enforcement personnel either in-person, by phone, or were mailed a letter and had agreed to re-engage with the criminal legal system. The researchers also conducted qualitative interviews with 12 advocates who provided advocacy and support to the Detroit survivors throughout the victim notification process.

“I’d like to stress how important it is to have advocates at the table from the beginning when informing survivors with previously untested sexual assault kits,” said project lead Dr. Katie Gregory. “When advocates weren’t there, the survivors noticed. It compounded the trauma for many survivors.”

Key Guidance

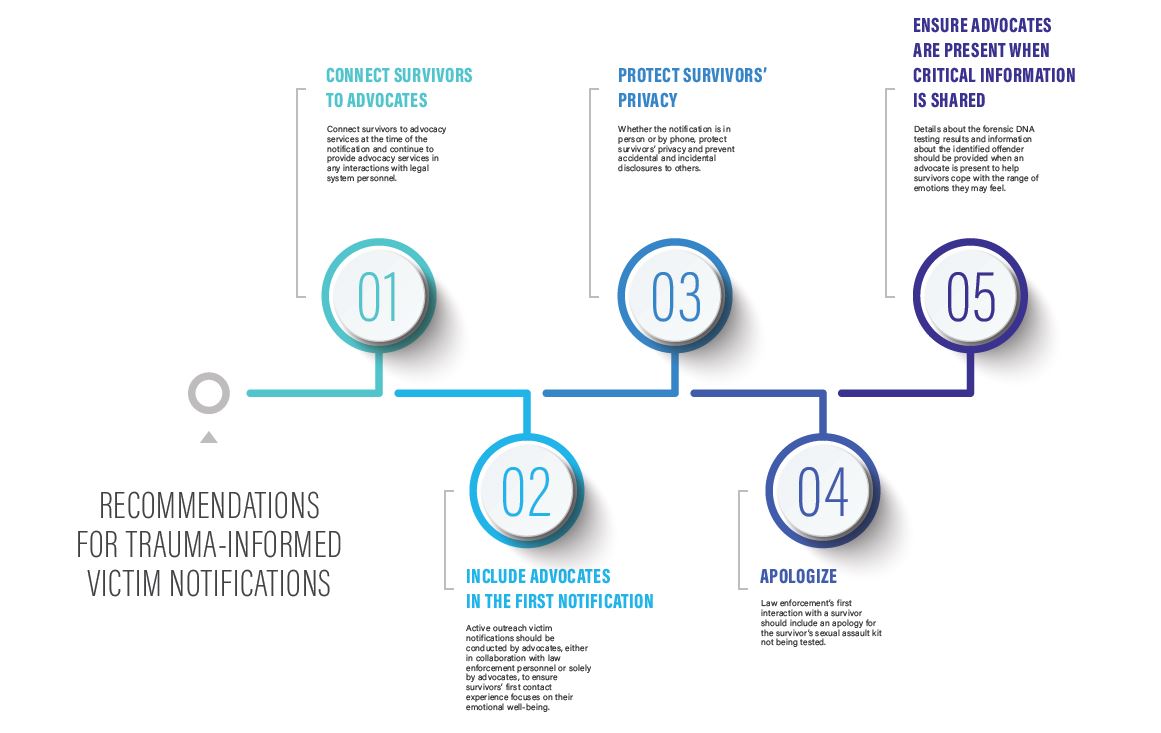

By analyzing the survivor and advocate interviews, the team was able to provide key suggestions for how other notification teams can be better trauma-informed.

Survivors shared that in-person notifications conducted by law enforcement personnel were frightening. Because of this, survivors and advocates recommended that advocates make the first contact with survivors either alone or with the detectives.

“An advocate is an advocate for the survivor,” said Dr. Campbell. “They are uniquely trained in how to listen and how to access the resources survivors truly want.”

By emphasizing that advocates are there for the survivors for as long as they are needed, to vent to or to help connect them with resources, survivors feel less alone in processing their trauma.

The interviews showed that having an advocate's support helped survivors cope with the range of emotions that they may have felt throughout the process, including at the time of notification and in any interactions with legal system personnel. At the time of notification, many victims reported feeling angry, betrayed, and disappointed—while also trying to take in the overwhelming details about their specific case.

Survivors and advocates also advised that receiving an apology from the detectives at the point of notification was essential in their healing process. In this study, only 13% of the interviewees stated that they received an apology from law enforcement.

From Detroit to Other Communities

Drs. Campbell and Gregory are using their findings from the Detroit study to inform similar research with Kalamazoo County through a grant from the Michigan State Police.

With the community being smaller, the Kalamazoo notification team can notify survivors on a case-by-case basis—by seeing if an in-person visit, a phone call, or a letter would be best for them. Another big difference: advocates are involved in the notification process from the very start.

“I hope that teams around the country who are grappling with how to connect with survivors understand that healing looks different for everyone. These notifications can be an opportunity to connect survivors with services and with people who can help,” said Dr. Gregory. “If you can keep that at the center of notifying victims, it can be an opportunity for healing.”

To learn more about the programs serving survivors at MSU and how to support survivors in your life, please visit supportmore.msu.edu.