Dedicated to Making a Difference: Transgender and Gender Diverse People Find Support in Trans-ilience

October 29, 2023 - Emily Springer, University Outreach and Engagement

This article initially appeared Volume 15, Issue 3 of Engage: The Engaged Scholar eNewsletter.

It’s Monday morning. Your alarm clock is set for 6:30, allowing enough time to double check your carry-on and enjoy a cup of coffee before heading to the airport to catch a 9:30 a.m. flight. Suddenly your subconscious jolts you awake only to come face-to-face with your clock reading 8:20 a.m., and the realization hits: You set your alarm for 6:30 p.m., not a.m. Thus begins the mad dash, leaving the thought of a leisurely cup of coffee in a whirlwind of dust you created while scrambling to get out the door.

It’s Monday morning. Your alarm clock is set for 6:30, allowing enough time to double check your carry-on and enjoy a cup of coffee before heading to the airport to catch a 9:30 a.m. flight. Suddenly your subconscious jolts you awake only to come face-to-face with your clock reading 8:20 a.m., and the realization hits: You set your alarm for 6:30 p.m., not a.m. Thus begins the mad dash, leaving the thought of a leisurely cup of coffee in a whirlwind of dust you created while scrambling to get out the door.

You get to the airport with 45 minutes to spare, show the TSA (Transportation Security Administration) agent your ticket and ID, and are waved through to your gate. You made it.

However, if you’re a transgender or gender diverse (TGD) person, interactions with TSA can add a traumatic layer to an already stressful morning. When interacting with the TSA and using your ID, the information about someone’s gender, legal name, or gender marker is sometimes used to target TGD people. This is just one of many examples of interactions that could lead to your being barraged with uncomfortable questioning, or worse, being the subject of ridicule or violence.

Jae Puckett, assistant professor of ecological-community psychology in the Department of Psychology, is researching the effects of exposure to these situations to develop new measures of stress and resilience that accurately reflect the lived experiences of TGD people.

“Historically, researchers have used models of minority stress that started with other populations, such as gay cisgender men, and then applied those models to TGD people,” Puckett said. “This left many gaps in the literature about the ways in which TGD people experience minority stress.

“Similarly, measures of resilience have typically been developed for general populations with little attention to how gender or living within oppressive social contexts may shape the experience and expression of resilience. What our team found through our own research, as well as past studies, was that resilience experienced by TGD individuals can include more novel aspects like self-defining one’s own gender experience, rejecting gender norms that don’t fit for that person, or engaging in advocacy.”

Through advancing research frameworks and measurement of TGD people’s experiences, Puckett’s research will pinpoint ways in which resilience can promote better outcomes and determine which factors help and hinder resilience over time.

Research Formed by Lived Experience

In addition to their other roles at MSU, Puckett directs Trans-ilience: The Transgender Stress and Resilience Research Team, which includes faculty, students, volunteers, and community members who are TGD or cisgender allies. Trans-ilience believes that TGD people should be included throughout this research process to ensure issues that are most important to the community are addressed.

Puckett and Trans-ilience focus much of their research on identified challenges and opportunities that are presented and discussed during meetings with Trans-ilience’s Community Advisory Board.

The board includes Lansing community residents, MSU students, professionals across various fields, and members of LGBTQ+ organizations in Lansing and the surrounding areas. These individuals identify issues they see in their everyday lives and speak to the importance of advocating for change.

“We’re not concerned about board members having research backgrounds or mental health backgrounds or health care backgrounds,” Puckett said. “We’re more interested in coming together around lived experience and having input in the local context.”

In recent discussions, the board identified current and prospective housing concerns as problems TGD individuals commonly face. There is not a wide array of research being done about TGD people and housing, and existing research focuses on the broader community, not the local community.

Kalei Glozier, a psychology graduate student in Clinical Science at MSU, works with Puckett and spoke about Trans-ilience’s efforts to overcome housing obstacles.

“One of the ways we’re tackling housing discrimination is by helping people correct legal documents related to their name and gender, making it less likely for individuals to be discriminated against based on gender identity,” Glozier said. “For example, a landlord may ask intrusive questions if the gender listed on your ID and gender presentation don’t match. However, if you’ve been able to legally update your documents, it’s less likely you’ll be discriminated against.”

Situations like those experienced with TSA agents and landlords can be seen and felt across a variety of areas, which speaks to the importance of Puckett’s study of those interactions—known as minority stressors.

“The TGD population experiences everyday stressors just like everyone else, but additional stressors can include being discriminated against, harassed, misgendered, or having to make decisions on who you disclose your identity to and who you don’t,” Puckett said.

To help combat these stressors, Trans-ilience is working with the Allen Neighborhood Center, a multifaceted hub for people living on the eastside of Lansing to access resources to improve their health and well-being.

Gender Affirmation Project

Together Trans-ilience and the Allen Neighborhood Center are implementing the Gender Affirmation Project, which provides practical and financial assistance to transgender and nonbinary individuals in Ingham County who are seeking to update their legal name and/or gender marker.

Glozier says research shows that having your name or gender marker changed can reduce stress. “If we can help people in our community go through the name change process, we are contributing to alleviating minority stressors, and we have the research to show just how important that is,” he said.

The process is lengthy, and it can be overwhelming for someone trying to navigate it alone.

According to Trans-ilience’s website, the requirements for a legal name change include a petition to the court, an abundance of confusing paperwork, publishing the notice of a legal name change in a newspaper, getting a background check, attending a court hearing, and paying fees. Beyond that, barriers can include having to interact with court officials and government employees who may ask intrusive questions or engage in discriminatory behaviors. In addition to extensive legal requirements and the potential for unwelcome interactions, a monetary barrier exists as the cost to affirm one’s gender is roughly $300.

Kat Logan, director of the Allen Neighborhood Center, said the Gender Affirmation Project can be life changing. “The project exists because of community members experiencing barriers in legally affirming their gender; the process is time-consuming, invasive, costly, and complicated,” Logan said. “But the documentation of one’s name and gender impacts almost all facets of life.”

Partnership with the Allen Neighborhood Center evolved naturally after Trans-ilience gave a community presentation there on how to best support trans and nonbinary community members.

“The center brings a rich set of skills rooted in community outreach and engagement, the social determinants of health, and on-the-ground efforts working with neighbors to empower our community,” Logan said. “Joining our skills and knowledge with those of Trans-ilience team members seemed like the right combination to really make a difference.”

The Allen Neighborhood Center provides a physical location for individuals seeking information about the Gender Affirmation Project to come and learn about the process for changing their name and/or gender marker.

“We have helped raise funds and leveraged our networks to spread the word about the Gender Affirmation Project, but ultimately our role is centered in providing guide-by-the-side assistance in completing required documentation, and writing the checks needed to move the process along,” Logan said.

Support for the project also comes from MSU’s Triangle Bar Association, a student organization dedicated to increasing social acceptance and providing support for LGBTQ+ staff, faculty, students, staff, families, and allies in the legal community.

Recently, with additional support from the Salus Center, an LGBTQ+ gathering space and resource center in Lansing, Trans-ilience, Allen Neighborhood Center, and MSU Bar Triangle Association held an event to raise funds to support the Gender Affirmation Project.

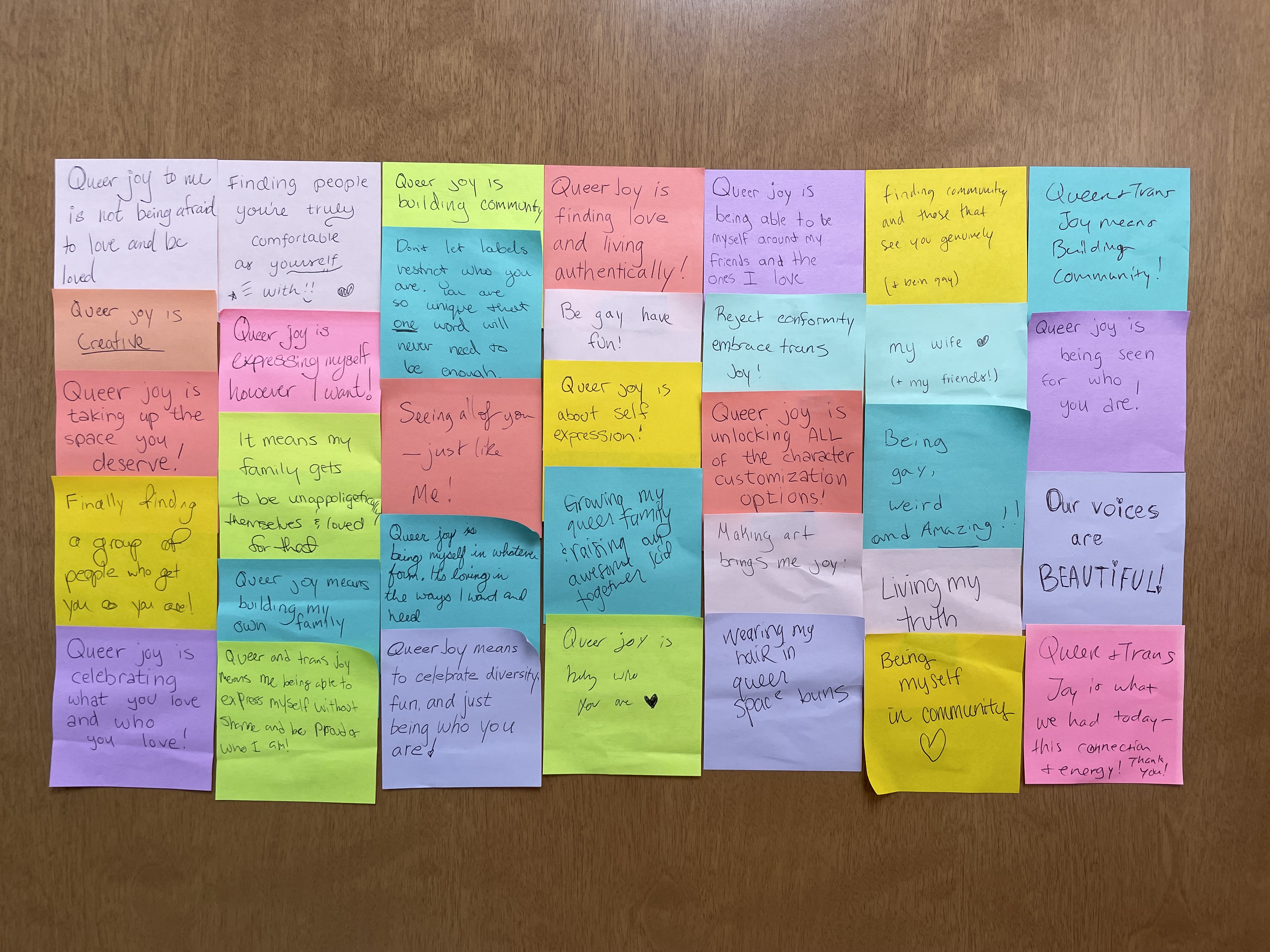

Attendees of the “Queer and Trans Joy Celebration” event spread support and encouragement by sharing what queer and trans joy means to them.

Their “Queer and Trans Joy Celebration” featured poets, dancers, singers, artists, and drag performers who shared their exceptional talents, stories, and songs with attendees. People were also able to take part in an activity to spread support by sharing what queer and trans joy means to them.

Prior fundraising efforts have assisted ten individuals complete the name change process through the project.

Puckett quoted one program participant who shared that changing their name and gender marker made a lasting impact. “I’m now able to walk in my own shoes and not have to worry about showing my ID,” the participant said. “I’m able to be 100% comfortable in my own skin.”

What’s Next

In addition to the Gender Affirmation Project, Puckett and the Trans-ilience team have remained steadfast in their dedication to research with practical implications, conducting many studies with an eye toward how their findings can be used in TGD communities.

One of Trans-ilience’s core beliefs is that their research should help inform social change and assist with creating positive and empowering social contexts for TGD people to live and thrive. They’re committed to doing that through continuing partnerships with TGD individuals, disseminating research findings through creative means, conveying findings to legislators, school boards, administrators, and taking the research from academia to the communities they work with.

“I’m excited for future research to do a better job reflecting TGD people’s experiences via our measure development that has been guided by community-engaged work,” Puckett said. “And I’m looking forward to more of the work our team is doing to contribute to social change and positive impacts within the communities we live in.”

For additional information about the work the Trans-ilience team is doing, visit the research page of their website.

Glossary of terms

Transgender or gender diverse (TGD): Those who have a gender identity that differs from that typically associated with their assigned sex at birth. This umbrella term includes those who identify and express their gender outside of the gender binary.

Cisgender: Those whose gender aligns with that typically associated with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Gender marker: A gender marker, sometimes called a sex marker or sex designator, is a designation on an identifying document or in a database as male, female, nonbinary, undisclosed, X, etc.

Self-defining gender experience: This refers to a person’s deeply felt, internal, and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond to the person’s physiology or designated sex at birth.