Autism Awareness Month: A Behavioral Neuroscientist’s Insights on Social Play

April 25, 2024 - Shelly DeJong

What’s going on in your brain when you’re navigating social situations? And how exactly are social behaviors developed and regulated by the brain?

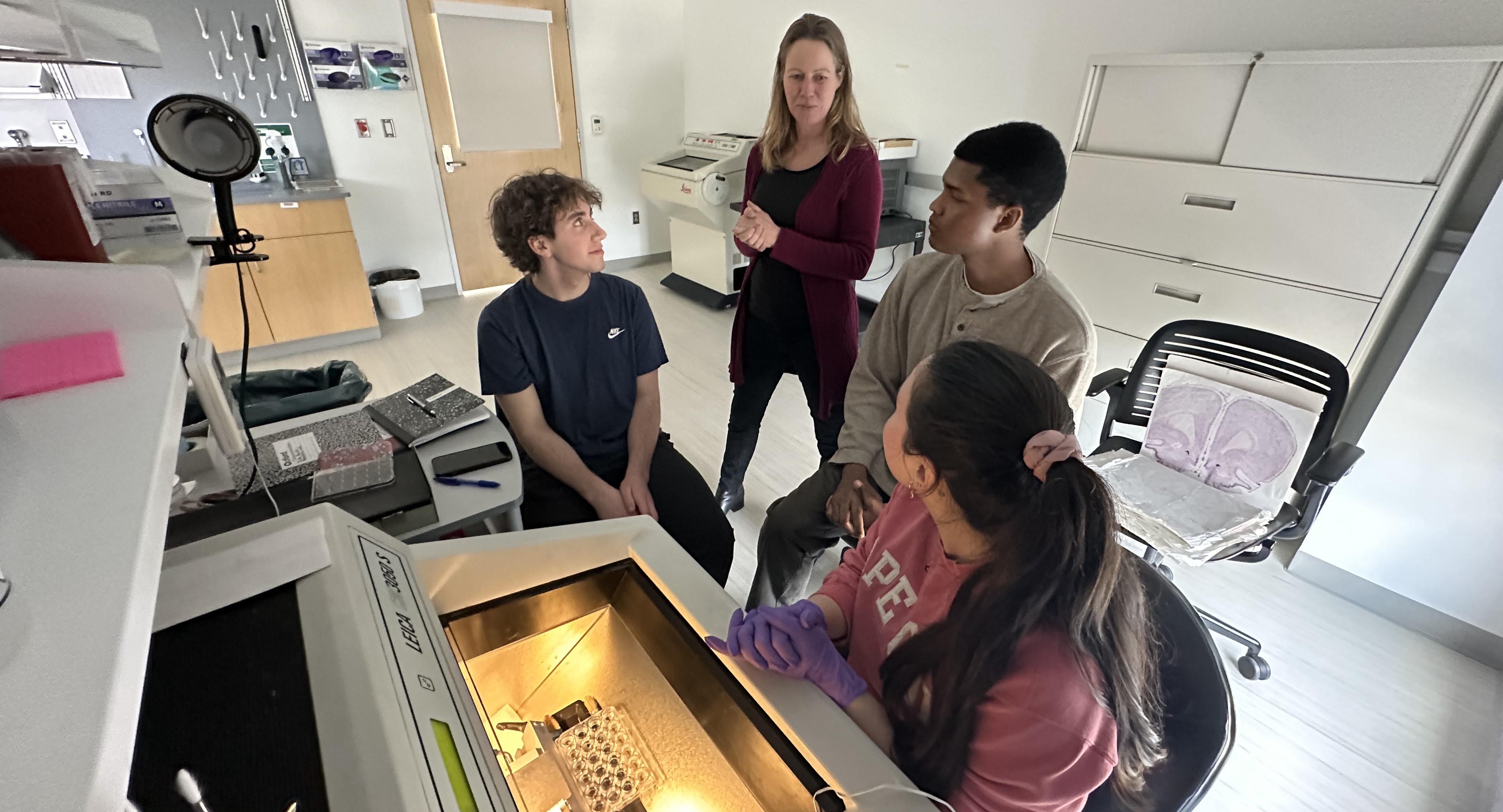

Dr. Alexa Veenema, a behavioral neuroscientist, was first intrigued by these questions during a postdoctoral position at the University of Regensburg in Germany. As a graduate student at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, she had studied aggressive behavior but found herself increasingly interested in social play during adolescence. Now with her own lab at Michigan State, she strives to shed light on the brain’s mechanisms behind social behavior, especially social play behavior.

“We as human beings crave social contact. We have multiple social contexts varying from casual to intimate. I’m intrigued by how the brain regulates appropriate behaviors in each of these settings. Autistic individuals find social interactions more challenging and less rewarding. Understanding how our brains learn to navigate complex social situations may help improve the lives of autistic individuals as well. And this starts already very early in life,” said Veenema.

“We as human beings crave social contact. We have multiple social contexts varying from casual to intimate. I’m intrigued by how the brain regulates appropriate behaviors in each of these settings. Autistic individuals find social interactions more challenging and less rewarding. Understanding how our brains learn to navigate complex social situations may help improve the lives of autistic individuals as well. And this starts already very early in life,” said Veenema.

Veenema explained that studies in rodents, non-human primates, and humans all show a positive impact on young animals or children exposed to social play with their peers, including better social skills and social competence. Without this exposure, rats end up being aggressive in inappropriate contexts. Adolescence is a vital time for children, rats, and other animals to be exposed to certain stimuli like peer physical contact.

“In today’s digital world, kids often end up having fewer physical interactions with their peers. This means that as kids are growing, there are fewer opportunities for kids to learn from each other on what is appropriate and what is not,” said Veenema. “We also know that autistic children have less motivation to engage in social play and they often have lifelong difficulties with social functioning.”

By knowing how the brain learns and regulates social behavior like play, the lab hopes to positively impact the scientific understanding of why this occurs in autistic children. While her lab works on preclinical research, Veenema values knowing that her lab can provide insights that can be useful for the autism research community.

What’s going on in the brain

The Veenema Lab focuses on exploring two neuropeptides, vasopressin and oxytocin, that are released in the brain during social play behavior. These two neuropeptides are already being used in clinical trials to determine their efficacy to improve social competence in autistic individuals.

“These two neuropeptides are already used in clinical trials without there being a lot of knowledge about what they do in a brain, especially in the still developing brain. Our research is trying to fill that gap,” said Veenema.

The Veenema Lab also focuses on sex differences, since they discovered that both neuropeptides act differently to regulate social play behavior in male juvenile rats compared to female juvenile rats. They hope to further research outside the gender binary as well.

The Veenema Lab also focuses on sex differences, since they discovered that both neuropeptides act differently to regulate social play behavior in male juvenile rats compared to female juvenile rats. They hope to further research outside the gender binary as well.

In a recent study on oxytocin, the Veenema Lab found that if they activated oxytocin neurons in the brain, social play behavior went down in males, but it went up in females. They found something similar for the vasopressin system when they blocked receptors in specific brain regions. They found that if you block the receptors in males, social play goes up, but in females, social play goes down. This surprised the lab as they weren’t expecting opposing directions between males and females.

“This research is so important because it provides insights that may be helpful for autistic children that are currently being experimentally treated with oxytocin or vasopressin-related drugs,” said Veenema. “What could be good for one sex might be bad for another.”

The American Psychiatric Association reported that autism is diagnosed four times more often in males than in females. This means that males are dominant in research studies and experimental treatments. Research from the Veenema Lab, though, has suggested that different brain systems are used in males and females when it comes to social skill development, which means that autistic females may not be getting the treatment that they need.

In addition, their research has suggested that age plays a large factor as well. The lab showed that low vasopressin in juveniles is needed for social play behavior, while high vasopressin is needed in adults for typical adult behaviors. This could greatly impact the treatment that autistic individuals receive throughout their lifespan. The Veenema Lab hopes to receive research funding to determine if vasopressin is enabling the transition from immature social behavior to mature social behavior.

“Our research has yielded interesting and surprising findings that I believe are important and relevant to humans as well. It can inform and maybe improve the lives of autistic individuals,” said Veenema. “It’s vital that we get this base level of understanding right.”